Key points

- Surgeons adjust operating room lights every 7.5 min to deal with shadow reduction, with 97% of adjustments requiring a complete pause.

- Shadow dilution technology in overhead lights works for surface procedures, but it can’t eliminate shadows in deep surgical cavities.

- 80% of surgeons report poor lighting and persistent shadows present a direct patient safety risk.

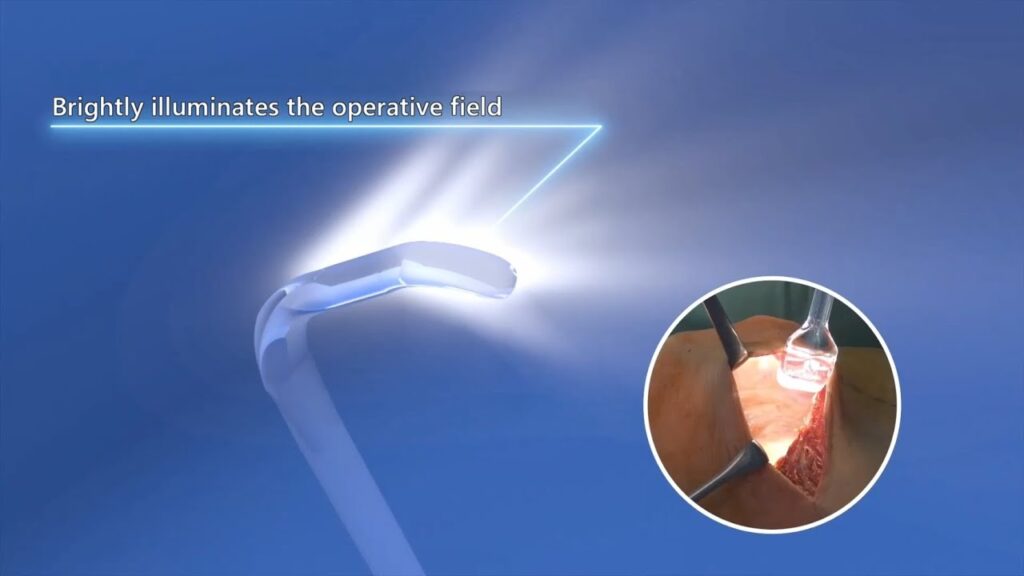

- In-cavity LED retractors, such as the Yasui koplight™, solve the shadow problem by positioning light inside the surgical field, where the inverse square law works in the surgeon’s favor.

- In breast surgery, shadow-free illumination from lighted retractors reduces skin flap damage and helps surgeons maintain flap and nipple integrity.

Surgeons adjust operating room lights every 7.5 minutes on average, and a study observing 46 hours of surgery across 13 hospitals found that 97% of these adjustments require a complete pause in surgical tasks. The problem isn’t inadequate equipment, since modern overhead surgical lights deliver 160,000 lux with color rendering indexes above 95. The problem is physics: light cannot illuminate what it cannot reach.

Shadows remain a persistent barrier to surgical visibility, particularly in deep cavities where the surgeon’s hands, head, and instruments block the path between overhead light and tissue. For medical device distributors evaluating surgical lighting products, understanding why shadows form and how different technologies address them helps position solutions to hospital procurement teams. For surgeons, the clinical stakes are documented: a Lifebox Foundation survey found that 80% of respondents reported poor lighting presents a direct patient safety risk.

Contents

Why do shadows form during surgery?

When any object sits between a light source and a surface, it blocks photons and creates a shadow, and in surgery, these objects include the surgeon’s hands, the surgical team’s heads, and the instruments themselves. Shadows have two components: the umbra, which is the region of complete darkness where all direct light is blocked, and the penumbra, which is the gradient zone of partial illumination surrounding it. A single point light source creates hard-edged umbra only, while extended light sources like the circular LED arrays in modern surgical luminaires generate softer penumbral regions that can be partially filled in by light arriving from other angles.

This principle, called shadow dilution, drives the design of overhead surgical lights. Multiple LED elements arranged in circular patterns create overlapping beams, so when one portion of the light is blocked, others illuminate the shadowed area from different angles. The IEC 60601-2-41 standard requires surgical luminaires to maintain at least 10% of their central illuminance when obstructions are present, and high-end systems achieve greater than 98% shadow dilution.

Shadow dilution has geometric limits, however, because it assumes light can actually reach the target tissue. In deep surgical cavities extending 20 to 30 centimeters below the surface, two factors combine to defeat even the best overhead systems. First, the surgeon’s body blocks the light path from above, and no amount of shadow dilution helps when the entire light source is obstructed. Second, the inverse square law governs light intensity over distance, so doubling the distance from light source to tissue reduces illumination to just 25% of its original value.

At typical overhead light distances of one meter or more, combined with cavity depth, the light reaching deep tissue planes may fall below clinically useful levels. For distributors, this physics has practical implications: shadow dilution works well for surface procedures, yet it creates a product gap in deep-cavity surgery that in-cavity lighting fills.

How do shadows affect surgical outcomes?

Poor surgical illumination isn’t a convenience problem; it’s a patient safety issue with documented consequences. The Lifebox Foundation survey of 100 surgeons across 39 countries found that 18% had direct experience of poor lighting contributing to negative patient outcomes, while another 32% reported delayed or cancelled operations due to lighting failures. These aren’t hypothetical risks; they’re documented clinical realities that affect both patients and surgical scheduling.

Shadows impair the visual tasks that define surgical precision. Tissue differentiation, which involves distinguishing pale nerves from surrounding fascia and identifying the boundary between healthy and diseased tissue, depends on subtle color and texture differences. The Color Rendering Index requirements in surgical lighting standards (CRI of 85 or higher, with 90 or higher recommended) exist specifically because accurate color reproduction allows these judgments, and when shadows obscure the surgical field, these cues disappear regardless of the light’s technical specifications.

Bleeding identification suffers similarly because early recognition of vascular injury depends on seeing color changes that shadows can mask. Assessing tissue oxygenation, which is critical in flap surgery and reconstructive procedures, requires consistent illumination across the field.

Surgeon health compounds the clinical picture. Studies report that 30% of surgeons experience eyestrain, and those with eyestrain are three to four times more likely to develop musculoskeletal disorders affecting the neck, shoulder, and back. The contrast between surgical light intensity (100,000 lux or more) and ambient operating room lighting (500–1,000 lux) forces constant visual adaptation, with the eye requiring up to two minutes to adjust when focus shifts between these zones.

Where do overhead surgical lights fall short?

Overhead surgical luminaires excel at their designed purpose: illuminating the general surgical field at or near the surface. Modern LED systems deliver 40,000 to 160,000 lux at one meter, adjustable color temperatures between 3,000K and 6,700K, and shadow dilution rates approaching 98%. The limitation isn’t performance within specifications; it’s the geometry of deep-cavity surgery.

When the surgical field extends into the body, the surgeon’s torso and arms occupy the space between overhead light and tissue. Repositioning lights takes time, and the observational study found that 64% of lighting adjustments interrupted surgical tasks, with 74% performed by surgeons and residents themselves rather than circulating staff.

Surgical headlights offer a partial solution by aligning illumination with the surgeon’s line of sight, so the light follows the surgeon’s attention and position, eliminating some shadows. Headlights create their own problems, however. A study of surgeons using headlights frequently found that 68% experienced aggravated neck symptoms, and 34% developed confirmed degenerative cervical disorders compared to just 7% of infrequent users. Fiber optic headlight cables also present thermal risks, with documentation of cables reaching temperatures up to 437°F within 10 minutes of operation.

The conclusion from surgical lighting research is that current operating room lighting methods each meet at least one critical illumination criterion, yet none meets all of them. Overhead lights and headlights each solve part of the problem, which means deep-cavity procedures require a third category of solution.

What is in-cavity surgical illumination?

In-cavity illumination positions the light source inside the surgical cavity, below the obstructions that create shadows from above. The concept isn’t new: in 1888, Roth and Reuss in Vienna used bent glass rods to channel light into body cavities. Modern implementations have evolved into two dominant technologies.

Fiber optic retractors transmit light from an external source through a cable to the retractor blade, with the light originating outside the surgical field and traveling to the tissue plane. LED-integrated retractors build battery-powered LED arrays directly into the instrument, so the light originates at or near the tissue and eliminates the external light path entirely.

The fundamental advantage of both approaches is the same: they bypass the geometric problem that defeats overhead lighting. When light originates inside the cavity, the surgeon’s body no longer blocks it, and the inverse square law, which works against overhead lights over distance, now works in the surgeon’s favor with the light source centimeters rather than meters from the target tissue.

In-cavity lighting represents a complementary technology rather than a replacement for overhead lights. Hospitals still need ceiling-mounted surgical luminaires for general field illumination, and in-cavity lighting addresses the specific, documented limitation those systems cannot overcome.

LED vs fiber optic: which technology performs better for lighted retractors?

Fiber optic illumination is established technology with decades of clinical use, and it can deliver high light output without requiring onboard power. It carries many documented drawbacks, which we get into in this article, however, that have driven a market shift toward LED-based systems.

Thermal risk presents the most serious concern with fiber optic systems. The FDA has received 307 complaints related to fiber optic surgical lighting since 1991, with 32 burn injuries reported between 2011 and 2021. The heat generated by light transmission through fiber bundles, concentrated at the cable and light source, can cause tissue damage during prolonged procedures.

Cable tethering restricts movement, adds clutter to the surgical field, and creates tripping hazards. Xenon light sources commonly used with fiber optic systems have lifespans of only 1,000–4,000 hours and fail suddenly rather than gradually, sometimes mid-procedure.

LED-integrated retractors address each of these limitations.

LEDs emit minimal heat, making them safe for prolonged tissue contact, and cordless operation eliminates cable management concerns. LED lifespan reaches 40,000 to 50,000 hours, with gradual dimming rather than sudden failure allowing planned replacement.

The total cost of ownership calculation favors LED systems as well because a reusable LED handle paired with single-use sterile blades spreads the lighting investment across many procedures while eliminating cross-contamination risk from the illumination component. For distributors, the technology trajectory is clear: hospital procurement teams increasingly specify LED-based in-cavity lighting for thermal safety, ergonomics, and lifecycle cost.

Why does breast surgery require in-cavity lighting?

Breast procedures illustrate the limitations of overhead lighting in clinical practice. Mastectomy, reconstruction, and augmentation all involve deep, narrow surgical pockets that extend in multiple directions: superiorly toward the clavicle, medially to the sternum, and laterally toward the latissimus. No single overhead light position can illuminate all these planes simultaneously.

A survey of breast surgeons found that 92% do not prefer headlights for these procedures, citing insufficient light for deep cavities, persistent shadows, and neck strain from the additional weight.

The clinical stakes in breast surgery are measured in millimeters. Skin flap viability depends on preserving adequate dermal thickness while removing sufficient breast tissue for oncological safety, and native mastectomy flap necrosis rates range from 5% to 41% depending on technique.

Clinical data from illuminated retractor systems report a 70% reduction in epidermolysis (blistering and skin damage) and 92% of surgeons noting increased success in maintaining flap and nipple integrity. The koplight™ cordless lighted retractor was developed with breast surgery as a key application, and its transparent polycarbonate blade transmits LED light to the underside of skin flaps, illuminating the precise tissue plane where preservation decisions are made. The cordless design eliminates cable burden during procedures that often exceed two hours.

Which other surgical specialties benefit from lighted retractors?

The illumination challenges documented in breast surgery extend across multiple specialties wherever surgical fields reach beyond overhead light penetration.

Thoracic and chest surgery, including funnel chest correction, requires illuminating wide yet recessed fields, and lighted retractors work effectively around wound protectors while providing consistent illumination as the surgical team’s positions shift. Oral and maxillofacial surgery involves confined spaces with additional constraints: patient eye exposure limits maximum illuminance, and fluoroscopy or CT guidance requires radiolucent instruments. LED retractors with plastic blades meet both requirements while delivering cold light that reduces tissue damage risk.

Plastic and reconstructive surgery depends on precise visualization of tissue planes during flap procedures, scar revision, and microsurgery, with the same flap viability concerns present in breast reconstruction applying here as well. Cardiovascular applications include radial artery harvesting for coronary bypass through minimally invasive incisions, where the narrow access window makes overhead illumination ineffective.

General surgery applications range from tracheotomy to laparoscopic procedures to musculoskeletal surgery, anywhere depth or access angle limits overhead light penetration. The koplight™ addresses this breadth with eight blade sizes that are switchable during procedures to match changing surgical requirements.

What should distributors evaluate when sourcing lighted retractors?

When assessing in-cavity lighting products for your portfolio, several factors warrant attention.

Regulatory status matters for market access, so confirm FDA registration, EU MDR 2017/745 compliance, and ISO 13485 certification for quality management systems. Illuminance output should meet clinical requirements, and you should verify lux ratings against the IEC 60601-2-41 reference range of 40,000 to 160,000 lux while recognizing that measurement methods for in-cavity devices differ from overhead luminaires. Thermal safety favors LED technology, and if you’re evaluating fiber optic systems, confirm thermal management specifications and review adverse event history.

Color rendering affects tissue differentiation, with CRI of 85 as the regulatory minimum and 90 or higher better supporting clinical decision-making. Blade and tip options determine specialty coverage, and a range of sizes increases facility-wide adoption potential while strengthening procurement conversations. The reusability model affects per-procedure economics, with reusable LED handles paired with single-use sterile blades balancing cost control with infection prevention.

Ergonomics influence surgeon acceptance because lighter instruments reduce hand fatigue during long procedures and cordless designs eliminate tethering. Manufacturing origin affects supply chain reliability, and Japanese manufacturing offers documented strengths in precision engineering, quality control rigor, and regulatory compliance.

Add in-cavity lighting to your surgical instrument portfolio

The koplight™ cordless lighted retractor addresses a documented clinical need: illuminating deep surgical cavities where overhead lights cannot reach. With eight blade configurations, FDA and EU MDR registration, and Japanese manufacturing, the koplight™ offers distributors a differentiated product backed by clinical evidence and regulatory credibility.

Contact Yasui to discuss distribution opportunities or request product samples for evaluation.